On a practical level, architecture exists to cater to one of the most basic human needs for survival. But in so doing, architecture tells stories, entrenches memories, interprets and helps us understand history, and thereby contributes in large measure to the very fabric of a place.

Following the destruction of Britain’s Commons Chamber during World War II, Winston Churchill famously said, “We shape our buildings, and afterwards, our buildings shape us.” Indeed, the spaces we inhabit play a significant role in moulding us as individuals, whether it be in the home or workplace, but to what extent does this impact our collective national identities?

On a smaller scale, some of the world’s bravest and most innovative architectural undertakings have been commissioned by companies determined to foster a sense of identity amongst its employees, and a means to extend its brand values. Take the recently completed Apple Campus by Foster + Partners for example. Its sleek, minimalist design mirrors what the brand is known and loved for. Or Bjarke Ingels’ Lego House in Billund, Denmark, which reimagines the popular toy bricks at architectural scale, communicating in its physical structure its core value - play.

Lego House: Iwan Baan

At the national level, in the African context, countries are bound to their colonial pasts most visibly by their architectural makeup. A big part of a previously colonised country’s identity is intertwined with its colonial history, and one could say the buildings still in existence are the memories of that painful past made visible. The history of colonialism in itself is traumatic, but it is part of what shapes us.

Now, how can nations reshape that narrative through architecture? The instance of Sir David Adjaye’s National Cathedral of Ghana is a step in the direction both in its use of an African architect to fulfill the project (a privilege we’ve only been afforded in recent years), and in its unapologetic proclamation that the country is ready to embrace its own identity.

Rendering of the Ghana National Cathedral: Adjaye Associates

Taking inspiration from Ghanaian Akan architecture and working side by side with local artists and artisans, Adjaye has designed what will stand as a globally recognised architectural landmark, proudly harking back to its own, authentic history.

“To rise, Africa has to aim beyond basic needs,” says Princeton professor of art history, Chika Okeke-Agulu. Which is to say that, the structures we build that reflect and inspire the parts of who we are, must become realities alongside the hospitals, schools, public spaces we need.

There is also the quandary of sacrificing national identity to modernity, which legendary architect Rem Koolhaas explored in his curation of the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale. But, he tells Architecture Australia, “the question of national identity is an open one.”

Wolff Architects’ Heinrich Wolff on the other hand argues that the concept of a coherent national identity is an imagined one. It’s an interesting consideration given the South African context, where a national identity is so hard to define because of its vast diversity. How do you inform such a national identity? Wolff says that factors like climate, region, religion, city, neighbourhood, history and creator take precedence over notions of a national identity to inform architecture. But are these not the things that make up a place’s identity?

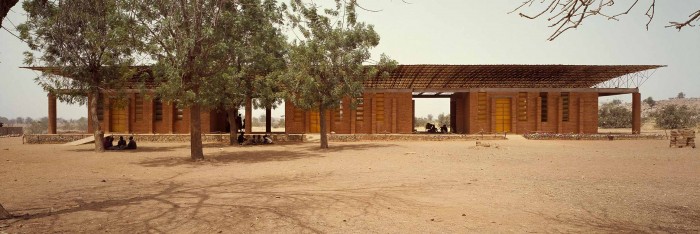

Gando Primary School: Kéré Architecture

When Diébédo Francis Kéré presented at Design Indaba Conference in 2011 he said, “The problem is, we’re copying the Western model, but we don’t know the story of it and we don’t own the means to make it happen in an appropriate way.” He points to a need to embrace all the elements that define a place and its story, and have that lead the design process, not rely on successes in immensely different contexts.

The UAE’s Dubai is an interesting case for the way architecture shapes identity. Widely recognised as a global city, the rich oil supplies in the region gave rise to a boom in its economy, population and prestige. This was accompanied by the construction of skyscrapers, commercial and residential buildings that today give the city its defining skyline. Its architectural makeup is reflective of the lavish Dubai life being marketed to the rest of the world, and of its cosmopolitan population.

Downtown Dubai and Burj Khalifa: David Rodrigo

The architects presenting at Design Indaba Conference 2019 defy tradition to carve a new forward, specific to the contexts within which they're designing.

More on architecture and identity:

Somali Architecture students are stitching back the country's heritage digitally

Swedish clinic designed with the country's refugee population in mind